Q: Does it make sense to borrow from my 401(k) if I need cash?

When cash is tight, your 401(k) can seem like a perfectly reasonable way to make life a little easier. The money is there and it’s yours—so why not tap it to pay off debt or get out of some other financial jam? Or you might be tempted to use it to pay for that dream vacation you deserve to take.

Stop right there. The cash in your 401(k) may be calling you—but so is your financial future. The real question here: Will taking the money today jeopardize your financial security tomorrow?

I’m not saying a 401(k) loan is always a bad idea. Sometimes, it may be your best option for handling a current cash need or an emergency. Interest rates are generally low (1 or 2 percent above the prime rate) and paperwork is minimal. But a 401(k) loan is just that—a loan. And it needs to be paid back with interest. Yes, you’re paying the interest to yourself, but you still have to come up with the money. What’s worse is that you pay yourself back with after-tax dollars that will be taxed again when you eventually withdraw the money—that’s double taxation!

If you’re disciplined, responsible, and can manage to pay back a 401(k) loan on time, great—a loan is better than a withdrawal, which will be subject to taxes and most likely a 10 percent penalty. But if you’re not—or if life somehow gets in the way of your ability to repay—it can be very costly. And don’t think it can’t happen. A 2012 study by Robert Litan and Hal Singer estimated defaults on 401(k) loans were up to $37 billion a year for 2008–2012 as a result of the recent recession. There’s a lot to think about.

Find Out If Your Plan Allows Loans

Many 401(k) plans allow you to borrow against them, but not all. The first thing you need to do is contact your plan administrator to find out if a loan is possible. You should be able to get a copy of the Summary Plan Description, which will give you the details. Even if your plan does allow loans, there may be special conditions regarding loan limitations. While there are legal parameters for 401(k) loans, each plan is different and can actually be stricter than the general laws. So get the facts before you start mentally spending the money.

Understand the Limits on How Much You Can Borrow

Just because you have a large balance in your 401(k) and your plan allows loans doesn’t mean you can borrow the whole amount. Loans from a 401(k) are limited to one-half the vested value of your account or a maximum of $50,000—whichever is less. If the vested amount is $10,000 or less, you can borrow up to the vested amount.

For the record, you’re always 100 percent vested in the contributions you make to your 401(k) as well as any earnings on your contributions. That’s your money. For a company match, that may not be the case. Even if your company puts the matching amount in your account each year, that money may vest over time, meaning that it may not be completely yours until you’ve worked for the company for a certain number of years.

Example: Let’s say you’ve worked for a company for four years and contributed $10,000 a year to your 401(k). Each year, your company has matched 5% of your contribution for an additional $500 per year. Your 401(k) balance (excluding any earnings) would be $42,000. However, the company’s vesting schedule states that after four years of service, you’re only 60% vested. So your vested balance would be $41,200 (your $40,000 in contributions plus 60% of the $2,000 company match). This means you could borrow up to 50% of that balance, or $20,600.

Now let’s say that after ten years of service, you’re fully vested and your balance has grown to $120,000. The maximum you could borrow is $50,000.

The government sets these loan limits, but plans can set stricter limitations, and some may have lower loan maximums. Again, be sure to check your plan policy.

Factor in When—and How—You Have to Pay It Back

You’re borrowing your own money, but you do have to pay it back on time. If you don’t, the loan is considered a taxable distribution and you’ll pay ordinary income taxes on it. If you’re under 59½, you’ll also be hit with a 10 percent penalty. Put that in real dollars: If you’re 55, in the 25 percent tax bracket, and you default on a $20,000 loan, it could potentially cost you $5,000 in taxes and $2,000 in penalties. That’s a pretty hefty price to pay for the use of your own money!

Before borrowing, figure out if you can comfortably pay back the loan. The maximum term of a 401(k) loan is five years unless you’re borrowing to buy a home, in which case it can be longer. Some employers allow you to repay faster, with no prepayment penalty. In any case, the repayment schedule is usually determined by your plan. Often, payments—with interest—are automatically deducted from your paychecks. At the very least, you must make payments quarterly. So ask yourself: If you’re short on cash now, where will you find the cash to repay the loan?

Think About What Would Happen If You Lost Your Job

This is really important. If you lose your job, or change jobs, you can’t take your 401(k) loan with you. In most cases you have to pay back the loan at termination or within sixty days of leaving your job. (Once again, the exact timing depends on the provisions of your plan.) This is a big consideration. If you need the loan in the first place, how will you have the money to pay it back on short notice? And if you fail to pay back the loan within the specified time period, the outstanding balance will likely be considered a distribution, again subject to income taxes and penalties, as I discussed above. So while you may feel secure in your job right now, you’d be wise to at least factor this possibility into your decision to borrow.

Smart Move: To lessen the odds of having to take a 401(k) loan, try to keep cash available to cover three to six months of essential living expenses in case of an emergency. (When you’re in retirement, you’ll want to have funds on hand to cover a minimum of a year’s expenses.)

Consider the Impact on Your Retirement Savings

Don’t forget that a 401(k) loan may give you access to ready cash, but it’s actually diminishing your retirement savings. First, you may have to sell stocks or bonds at an unfavorable price to free up the cash for the loan. In addition, you’re losing the potential for tax-deferred growth of your savings.

Also think about whether you’ll be able to contribute to your 401(k) while you are paying back the loan. A lot of people can’t, possibly derailing their savings even more.

Do You Qualify for a Hardship Distribution?

If your plan allows it, you might qualify for a hardship distribution. But doing so isn’t easy. First, you must prove what the IRS considers “immediate and heavy financial need.” In general, the IRS defines this as:

- Medical expenses for you, your spouse, or dependents

- Costs directly related to the purchase of your principal residence (excluding mortgage payments)

- Postsecondary tuition and related educational fees, including room and board for you, your spouse, or dependents

- Payments necessary to prevent you from being foreclosed on or evicted from your principal residence

- Funeral expenses

- Certain expenses relating to the repair of damage to your principal residence

The amount of the distribution is limited to your own contributions to the plan and possibly your employer’s contributions but doesn’t include earnings or income on your savings. It can’t be for more than the amount of the specific need—and you can’t have other resources available to cover it. Plus, you’ll have to pay both income taxes and a 10 percent penalty on the distribution.

Is There Any Way to Take an Early 401(k) Distribution Penalty-Free?

There are a few situations in which a penalty-free early distribution is allowed:

- You become disabled.

- You die and a payment is made to your beneficiary or estate.

- You pay for medical expenses exceeding 7.5 percent of your adjusted gross income.

- The distributions were required by a divorce decree or separation agreement (“qualified domestic relations order”).

As you can see, the IRS doesn’t make it easy to take your 401(k) money early under any circumstances!

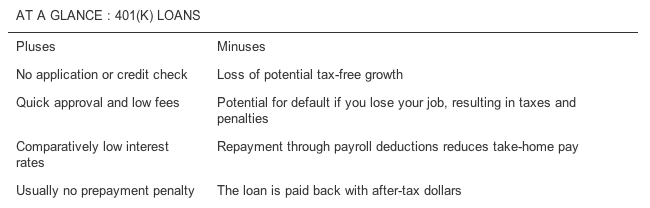

| Pluses | Minuses |

|---|---|

| No application or credit check | Loss of potential tax-free growth |

| Quick approval and low fees | Potential for default if you lose your job, resulting in taxes and penalties |

| Comparatively low interest rates | Repayment through payroll deductions reduces take-home pay |

| Usually no prepayment penalty | The loan is paid back with after-tax dollars |

Behind the Scenes: Multiple 401(k) Loans

Some plans allow you to carry more than one loan at a time. However, the maximum loan limits still apply—the lesser of one-half of the vested value of your account or $50,000. It gets a bit tricky because the otherwise maximum permissible loan is reduced by the highest outstanding loan balance during the twelve-month period ending the day prior to when the current loan was due.

Example: Let’s say you have $125,000 in vested benefits. You borrow $40,000 on January 1, 2014, and repay $25,000 on April 1. Then on December 1 of the same year, you want to take another loan. Even though you repaid part of your first loan, you would still be limited to a maximum second loan of $10,000 because your highest loan balance within the previous twelve months was $40,000 ($40,000 is subtracted from $50,000, or the maximum permissible loan amount). If you wait until April 2 of 2015, you’d be able to borrow $35,000 because your $25,000 payment would have been factored in and your highest loan balance in the prior twelve-month period would then be $15,000 ($15,000 subtracted from $50,000).

With multiple loans, it’s not just a question of how often you can borrow but how much you can borrow at a given time.

Part I: When Retirement Is at Least Ten Years Out, Question 8

Additional excerpts

- I just retired. What’s the smartest way to draw income from my portfolio?

- How can I save for my kids’ college without derailing my retirement?

- When should I file for Social Security benefits?

- Should I be debt-free before I retire?

- My husband has no interest in our finances. How can I get him involved?

- I’m confused about how to divide my estate between my children, who have different needs and financial resources. Is it best to divide it into equal parts?

- My 20-something child has decided that she wants to move back home. I like my new empty-nest lifestyle, but I want to help her out. How can I balance these?